April 2023 – Artist’s Studio Draft - Cover page

This Is Text Based Art

What is Text Based Art?

What do Global Art Critics Say About Text Based Art?

What’s the Art History of Text Based Art Worldwide?

How Does Art Theory Explain a Global Text Based Art?

Is A Global Language Possible in Text Based Art?

Are There Ways To Evaluate Text Based Art Worldwide And Across Languages?

Contents

Page 2

The Possibility of Text Based Art as a Common Art Language for Global Thinkers and Critics.

The Similarities Across Cultures are Striking.

Page 12

In Text-Based Art Histories Across Continents and Cultures, a Shared Global DNA.

Recognizing All Text-based Art Histories, Plural.

Page 18

How Will Critics and Viewers Evaluate Text Based Art as Sources of Words and Images Change?

Potential global standards and criteria for now, AI, and post-AI.

Page 22

Is This Text Based Art? A Critique of Works as Measured by and Through the Above Contexts.

Does it just say what you should think? Does it just look pretty on your wall?

Bibliography + About

Page 2

A. This Is Text Based Art: A Possible Common Art Language for Global Thinkers and Critics

Worldwide Perspectives On What Is Possible With Text-Based Art

The following overviews are only short summaries of just a few of the writings, theories, and criticisms of these art critics, curators, art theorists, art scholars, and artist-critics, who in turn are just a few of the thinkers and writers in these areas and fields worldwide. That said, based on research of them so far, my tentative conclusions about global text-based art include that—despite often fundamental and even acute differences in philosophical systems, thinking systems, religious influences, and political, economic, and social structures and assumptions, text-based art is (a) evidenced as an art form almost everywhere on the planet for (b) many of the same philosophical, artistic, and concrete reasons.

Broadly speaking, those reasons appear to be that text-based art—loosely and broadly defined here as any visual art that uses words, language, characters, or language-symbols in some way—affords artists, no matter where they are globally, across continents, countries, and cultures, an artistic aesthetic and a means of artistic expression that can address, explore, and wonder with curiosity about:

· Our most concrete and present issues and needs;

· Our most abstract and philosophical questions about both the intellectual head and the emotional heart;

· Our questions about our languages themselves; and

· Our questions about art itself, including, what is art?

Asia

China

The Chinese art critic and curator Li Xianting, who has also made contributions to avant-garde art in China, might view text-based art primarily as associated with activist art, as a means of challenging established cultural and political norms, using language as a tool not just of critique but also of various degrees of subversion. He might be among those global art critics who take interest in text-based artists who use language in innovative and even imaginary ways, such as Xu Bing, the artist, professor, MacArthur Fellow, and former vice-president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, who has used text and fictitious Chinese characters to question the reliability of communicating through any language, on the theory that the very nature of language allows not just for ambiguities and interpretation but also profound exploitation and manipulation.

Japan

The Japanese contemporary artist and critic Yoshitomo Nara, whose work is seen to be able to bridge both high art and low art, and both the East and the West, might see text-based art not just as an art form for expressing social and political commentary, but also as a way to express personal and human feelings in a complex way. Nara might also see text-based art useful both aesthetically and conceptually as a means of disrupting not only traditional forms and mediums of art, but also as a means of disrupting a viewer’s assumptions and expectations, such as by text works that offer an initial illusion of one set of emotions, feelings, or ideas, but in fact offer interpretations inviting contemplation of very different emotions or ideas. Nara might also see text-based art as being able to push boundaries of what is considered to be art, and as a way to disrupt traditional forms of visual art.

Vietnam

Vietnamese art critic Phan Cam Thuong, who has written on the intersection of art and politics, might see text-based art as a way to challenge the dominant narratives and ideologies, and further as a means of political dissent through the possible use of art and text to subvert traditional and entrenched power structures. Thuong might also see text-based art as a means by which artists can both document and amplify the voices and traditions of marginalized communities and cultural groups in Vietnam.

Africa

Ethiopia

The Ethiopian curator, anthropologist, and writer Meskerem Assegued, who was a member of the selection committee for the 2007 Venice Biennale African Pavilion, and who has written on contemporary art practices in Ethiopia and Africa, might see text-based art as an art form that allows artists to offer interpretations about the interaction between language, culture, and identity in Ethiopia. Her writings suggest that she might also see text-based art as a way to challenge traditional notions of Ethiopian art and culture and to create spaces for marginalized voices, and might see ways in which text-based art can be used to create new forms of expression to engage with complex political and social issues in Ethiopia, and perhaps also across the continent.

Nigeria

Chika Okeke-Agulu, the artist, art historian, Princeton University professor, and British Academy Fellow, is a Nigerian art critic and curator who has written about, and curated shows about, several aspects of contemporary art in Nigeria, as well as art during late twentieth-century dictatorships in Nigeria. Based on his publications, he might see art with words as an artistic expression through which artists can experiment with, and offer, new possible meanings, open to interpretations, about not just contemporary Nigeria but also the historical relationships between language, culture, and identity within Nigeria, specifically the intersection of globalization with Nigeria’s cultures and identities, as well as issues in Nigeria during and after colonialism.

Tunisia

The Tunisian art critic and poet Souad Guellouz, and the Tunisian art critic Sonia Hamza, might each see text-based art as an artistic medium that could be used to express complexities of contemporary Tunisian society—such as Tunisia’s intersections between Tunisia’s art and politics, its traditions as juxtaposed against its modern norms, between past and present modes of thinking, and between the individual as distinct from the collective. They might also see text-based art as a way to create new modes of language expression that not only reflect realities and possibilities of Tunisia, but which also provide for greater world access to Tunisia’s contemporary art and contemporary artists, a point especially made in art criticism writings by Hamza.

Uganda

The Ugandan art critic Eria Solomon Nsubuga, known as SANE, is a contemporary Ugandan painter and art lecturer. With a chosen designation as a social artist, and given that his practice explores the politics of climate, allocation of natural resources, morality, and spirituality, he might see text-based art as a form or medium of art that can provide not only for social and political critique—and more specifically as a way to challenge the status quo and to raise awareness about structural inequalities in Ugandan society—but also as a way to invite new perspectives on traditional notions of spiritual and religious iconography, beliefs about resource possession, and the contradiction of corruption within leaders claiming to be of religious faith. For Nsubuga, text-based art might be a way to give voice to both people and to issues that are marginalized and silenced, as well as to be an affirmative means for social and political change with respect to some of the concrete issues mentioned above.

Central America

Guatemala

The Guatemalan poet and art critic Luis Cardoza y Aragón might see the use of language as a medium itself in the context of art, and might see text-based art as a way to explore the relationship between image and word as a function of visual and linguistic aspects of communication. He might also see the use of text in art as a way to connect with cultural and historical literary traditions.

Eastern Europe

Poland

Karol Irzykowski, a Polish critic who wrote about both film and visual arts, might have seen text-based art as a form of visual poetry, where text stands not just for its linguistic meanings but also for its own aesthetic qualities, depending how presented.

Global Indigenous Peoples

Cree

The Cree scholar, writer, and artist Karyn Recollet, who has written about the intersection of art, activism, and decolonization, often in connection with modern urban spaces, might see text-based art as an aesthetic vehicle for engaging with these topics and issues, possibly using language in text art for both conversation and resistance. She might find of interest those text artists who incorporate text into their practices as a means of challenging dominant narratives, while at the same time promoting disenfranchised cultures, knowledge systems, and perspectives. For example, she might favorably view the work of Anishinaabe artist Maria Hupfield, whose works with text address some of these issues in the context of cultural identity and political power.

Māori

The Māori scholar, professor, and critic Linda Tuhiwai Smith has written on the relationship between Western and Indigenous knowledge systems, including critical analyses of how Western scholarly research paradigms impede social justice during the colonialization of indigenous cultures. Professor Smith might see text-based art as holding the possibility of critiquing the intersections of language, culture, identity, social justice, and colonialization of societies, with an emphasis of documenting not just indigenous languages and but also indigenous knowledge systems. As such, she might be interested in text artists who both preserve indigenous knowledge and culture and also affirmatively assert it, such as the Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore, whose text-based visual works have addressed some of the types of colonialism and identity issues that Professor Smith has written about and critiqued.

Pueblo

The Pueblo poet and writer Simon Ortiz, known in part for his participation in the second wave of the Native American Renaissance, and who has written on issues of Indigenous identity and culture, including the preservation of literary and oral histories, might see text-based art as a form of art capable of not just preserving those histories but also engaging with them, to document perspectives and present new interpretations. He might see with interest the work of text artist Marie Watt, who is enrolled in the Seneca Nation of Indians, who sometimes uses text and symbols in exploring the full diversity of Northern Hemisphere Native American histories and mythologies in her practice.

India

The Indian curator and art critic Geeta Kapur, known for her writings on modern and contemporary art in India, might see text-based art as an aesthetic useful for exploring assumptions within language, identity, and power. She might find of interest artists who use language to reclaim lost or misappropriated cultural and historical narratives, such as the contemporary Indian artist Nalini Malani, whose practice sometimes uses words and phrases in her visual works on these subjects in India.

The Indian art critic Ranjit Hoskote might see text-based art as a tool for political and social critique, specifically as a way to both challenge the status quo and attempt to subvert dominant political power structures. Hoskote might also see text-based art as a way to explore the intersections between art, politics, and society, and to question cultural assumptions that underlie them.

Middle East

Egypt

The Egyptian art critic Tarek El-Ariss, who has written on the intersection of art, literature, and politics, might, like other critics discussed here, see text-based art as a medium of expression uniquely able to expressly discuss relationships between language, power, and identities in Egypt. He might also see text-based art as a means of challenging established narratives of Egyptian society by creating new artistic spaces for marginalized voices. He might also focus on the ways in which text-based art could be used to explore nuances of Egyptian culture to create a more inclusive and diverse art scene in both Egypt.

Iran

Shahram Karimi is an artist and art critic in Iran who has written about the relationships and interplay of art and broader culture. Karimi might see art with words as allowing artists a means of exploring complexities in the relationships between language itself and broader cultural and historical identities. Like other art critics and scholars discussed here, he might see text-based art as a means of confronting established or entrenched cultural narratives in order to explore under-represented voices in Iranian society. Karimi might particularly appreciate the ways in which text-based art can be used by artists to express emotions and ideas in ambiguous layers that can be interpreted in different ways to engage viewers with elements of Iranian culture.

Iraq

The Iraqi art critic Nada Shabout might view text-based art as an artistic medium for investigating the cultural and historical facts of contemporary Iraq and the Arab world. She might see text-based art as a way to present new narratives that shape a viewer’s understanding of Iraq, and more broadly the Middle East, and to create and express alternative viewpoints that reflect the broader diversity and fuller richness of Iraq’s many cultures and voices. For Shabout, text-based art might be a way to reclaim the histories and cultural heritages within Iraq, and to both document as well as amplify its internal histories in the context of the larger world.

Ali Assaf, another Iraqi artist who has written on contemporary art practices in the Middle East, might see text-based art as useful for exploring the same intersections identified by other art critics, including the intersections of language, culture, and identity in Iraq. He might focus particularly on text-based art in the context of amplifying marginalized voices and in the context of creating new forms of contemporary expression altogether, to examine contemporary political and social issues in Iraq.

Tamara Chalabi is a third Iraqi art critic who is also known for her engagement with contemporary art practices in Iraq. Like other critics discussed in this paper, Chalabi might likely see text-based art as important not just as a form or genre of art, but for serving as a form of expression that can engage with relationships between language, culture, voices, and identities in Iraq. She might see text art specifically as an aesthetic form that can also question traditional notions of Iraqi art, as well as the notion of art itself.

Israel

The Israeli art critic Gideon Ofrat, who has written about the relationships between art and politics, might see text-based art as a way to explore the complex political and cultural relationships between Israeli and Palestinian identities. He might particularly see text-based art as a means of documenting and juxtaposing the contemporary and historical perspectives of both Israeli and Palestinian voices. Ofrat might also consider text art as possibly facilitating new perspectives for dialogue and understanding.

Palestine

The Palestinian art critic Kamal Boullata might have seen art with words as an artistic medium able to both express and document experiences of displacement. He particularly might have seen text-based art as a way to articulate emotions and feelings about contemporary political experiences in relation to identity and place. He might also have seen text art as a form of aesthetic expression that can explore relationships between cultural histories, political histories, and cultural memories, including across borders. He might have seen text-based art as uniquely available to create layered and ambiguous meanings allowing for new interpretations of complex political dynamics across borders, and, more broadly, throughout that region of the world.

Turkey

Levent Çalıkoğlu is an art critic in Turkey who engages with contemporary art practices. Çalıkoğlu might view text art, like other critics in this paper, as a way to explore the relationships between language, culture, and identity. He might also see text-based art as a means of affirmatively challenging the power dynamics of languages themselves, and as a way to create new visual-symbolic modes of communication. Like others, Çalıkoğlu might also appreciate the ways in which text-based art can be used to create ambiguous and layered meanings, to afford new interpretations of complex political and cultural issues in Turkey.

Saudi Arabia

Ahmed Mater, the Saudi artist, writer, and art critic, who is known for his engagement with contemporary art practices on each of these levels, might see art with words and language as a way not just to explore the intersections of religion, culture, and identities in Saudi Arabia, but also of demonstrating and challenging the entrenched power dynamics of languages themselves.

Syria

Murtaza Vali is a Syrian art critic who writes on contemporary art practices in the Middle East. Like many others discussed in this paper, Vali might see text-based art as a means of considering how language, culture, and identity interact. He might particularly see text-based art as offering a medium to investigate traditional notions of Syrian art and culture relative to more contemporary views and voices. And like many other critics discussed here, Vali might appreciate that text-based art can be used by artists to create new forms of aesthetic expression that engage complex political and social issues within a country.

North America

Canada

Sarah Milroy is a Canadian art critic who writes about contemporary Canadian art. Like many discussed here, she might see text-based art as an aesthetic for exploring human intersections in her country, including how Canada’s multiple histories, languages, and identities interact. She might particularly view art with words and language as engaging with Canada’s histories with respect to cultures, including with respect to Indigenous peoples, that exist across Canada’s vast geographical space.

Cuba

Tamara Diaz Bringas, as both a Cuban art curator and as an art critic, might see text-based art as a way to engage with the political and social realities of contemporary Cuba. She might also see the potential for text-based art to address issues such as censorship, surveillance, and political repression, as well as to celebrate resilience and creativity in Cuban culture. She might also see the use of text in art as a way to connect with the history of literary expression, and all artistic expression, in Cuba.

Mexico

The art historian and art critic Raquel Tibol, who was born in Argentina and who died in Mexico City, and who wrote on Mexican and Latin American art, with a focus on social and political issues, might have seen text-based art as affording artists the possibility of engaging in new ways with issues of cultural identity and issues of national politics, using language to expressly critique dominant ideologies in order to encourage actions towards social change. Tibol might have been most interested in text artists who use language as a means of expressly engaging with specific cultural and historical contexts, such as some of the muralists of the 1920s and 1930s who employed text and language, including at times Diego Rivera, as well as artists who used language to challenge false narratives and assumptions supporting dominant norms of colonialism and imperialism.

The Mexican writer, poet, diplomat, and cultural critic Octavio Paz, whose writings included analyses on the intersections of Mexican art, literature, and politics, might have seen text-based art as allowing a wide range of artists to explore nuances of the most complex aspects of language, identity, and power. He might have been interested in artists who use text and language to not just document and but also call attention to marginalization and exploitation, as well as artists who employ language as a means of reclaiming cultural heritages, such as muralists of the 1960s and 1970s.

The Mexican muralist and painter Jose Clemente Orozco, known for politically charged artworks addressing social and political issues in Mexico and beyond, might see text-based art as a direct vehicle allowing artists and viewers alike to engage these issues, with word art enabling new uses and interpretations of language for the purpose of critique and subversion. He might be interested in artists who use text in a bold and provocative manner in the context of political, social, and cultural issues and assumptions, such the American text-based artist Barbara Kruger, whose large-scale installations and text-imagery works question power dynamics and artificial constructions in contemporary society relating to identity, sexuality, and consumerism.

The Mexican art critic and curator Marta Elena Bravo, who has written on contemporary art in Mexico and Latin America, might see text-based art as directly engaging with concepts of cultural identities and political power, using language both to critique dominant narratives and to offer new interpretations for social change. She might find of interest artists who use text as a means of exploring the full complexities of Mexican and Latin American cultures, such as the Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco, whose works sometimes employ text with cultural artifacts to address not just identity, migration, and globalization, but also to blur ideas of the boundaries of art itself.

United States

Rosalind Krauss, the American art critic, art theorist, and professor at Columbia University in New York, and a leading figure in the field of modern and contemporary art theory, had an analytic approach that emphasized both the ideas of French post-structuralist thinkers, like Jacques Derrida, discussed below, as well as the importance of the role of the viewer in the interpretation and meaning-making of art. In her theory of analysis, a work of art is not fixed or determined exclusively by the intentions of the artist alone, but rather is also constructed through and by the viewer's interaction with the work.

In terms of aesthetics, Krauss might be interested in the ways that text-based art expressly challenges traditional notions of visual art (in all forms, including both figurative and abstract) and expands the theoretical and concrete possibilities of what art itself can be. She would likely emphasize the importance of considering the formal qualities of text-based art, such as work’s use of typography, materials, and composition, in addition to its substantive content.

In terms of a theoretical perspective, Krauss might be most interested in the ways that text-based art intersects with language and literature, and how it engages with issues of meaning itself, and also the nature of communication itself. She might draw on these to explore the ways that—and reasons why—language is inherently unstable and subject to multiple interpretations.

In terms of possibilities, Krauss might be interested in the ways that text-based art can be used to explore an unusually wide range of subjects and themes, from political and social commentary to personal expression, human feelings, and human emotions and intuitions. She might likely see text-based art as both a theoretically and practically valuable form of artistic expression that challenges traditional boundaries between art forms—and also successfully invites viewers to actively engage both with and in the meaning-making of text-based work.

Separately, the American art critic Jerry Saltz has written that he sees text-based art has having a robust history that stretches back to the earliest known examples of human expression. He might note that from ancient cuneiform tablets to modern-day graffiti, text has always played a vital role visual arts across mediums. He might say that, while there is a risk that text-based art can be didactic, or prone to teach, declare, or explain, rather than allowing for interpretation, what sets text-based art apart from other aesthetics is its ability to convey complex ideas and emotions through language and hybrids of language and image, as well as its potential to engage the viewer on both a visual and intellectual level through ambiguity and interpretation. Saltz might also write that text-based art offers a unique opportunity for artists and viewers to explore the intersections between language and image, and to push the boundaries of what a given society or culture considers to be art.

Given some of his writings, Saltz might argue that with the rise of both digital media and the beginning of the democratization of the art world, text-based art has become an increasingly important form of diverse visual expression, and one that has the potential to challenge our assumptions about who makes art, what art is, and what it can do both as an art form and as an element giving voice in unique ways in broader society.

Separately, the American art critic, poet, and educator Peter Schjeldahl might focus the risks of text-based art limitations while also seeing its possibilities. Specifically, he at times wrote that some text-based artists might lapse into the limitations inherent in all language forms, in that, depending on how approached, language-based art can be difficult for a viewer to engage with if it becomes didactic, or narrowly focused on teaching, telling, explaining, or otherwise becoming declarative. He has also written that text-based art can lapse into being overly intellectual, at least to his critical tastes, by prioritizing a substantive message over the viewer’s aesthetic experience with a work. He has also noted in his writings that text-based art for some viewers can be difficult to read or interpret, particularly where there are barriers across languages or references.

With the above risks and potential limitations in mind, Schjeldahl has also written that the promise and possibilities of text-based art exist at their fullest where an artist uses a given language and the forms of letters, characters, symbols, and words not just for expression of concrete subjects and themes, like social justice or specific political commentary, but also for reflexive questions looking inwards and introspectively on issues relevant to art itself, and language itself, including questions such as (1) what are the boundaries of visual art and language in relation to meaning; (2) where are the lines between didactic declarations and ambiguities that invite viewer interpretation; and (3) whether there are overlapping spaces in text-based art that are not just intellectually engaging but also emotionally and even spiritually engaging, even across borders and language differences.

Russia

The Russian art critic Boris Groys, who has written on the relationship between art and politics, might note some of the same theoretical points raised by Krauss, Saltz, and Schjeldahl, particularly as to the risk of text-based art resulting in works that are didactic, but given some of his writings he might still see text-based art as a powerful concrete artistic tool for political commentary and activism. His writings suggest a focus on art with words as having a unique ability to convey messages and ideas in a direct and impactful way as to both a particular viewer and as to a culture or society as a whole. Groy would likely observe text-based art as having potential because of its history, in that text, or text concepts, have played a lasting role in the development of art from the earliest symbolic cave paintings and rock etchings to the present day. He might also see the use of text in visual art as allowing for a range of artistic and aesthetic approaches, from straightforward communication without deeper meanings to more abstract and ambiguous messaging not just as to facts or views but also emotions and feelings.

Groy’s writings suggest that he would see text-based art as being able to incorporate other forms of media, such as video or sound, to create an immersive experience for the viewer using multiple senses and multiple parts of the brain, including the intuitive and the logical, particularly as new technologies emerge allowing artists using text to continue to push and blur the boundaries between art mediums, causing text-based art to remain a profound component of broader collective notions of art.

Aleksandr Benois was a Russian art critic who might have viewed text-based art as a unique way to express not just the concrete and the material but also, particularly, the spiritual and emotional dimensions of humanity and of art itself. He might see text-based art as a means to most clearly convey to the viewer the inner world of the artist, and the way to most clearly capture and share the essence of human experiences and ideas. Based on his writings, it appears that, for Benois, text-based art would be a way to bridge the assumed divide in some thought systems between the external world of objects, things, and reason, on the one hand, and the internal world of emotions, feelings, and intuition, on the other hand.

South America

Argentina

The Argentine art critic Marta Bravo might see the possibilities of text-based art in relation to the medium’s ability to explore and communicate ideas relating to political and cultural implications of dominant societal norms. She might view artists using text as being able to find a way to communicate social and political commentary through hybrid language-visual means, allowing an artist who uses text and image to more fully and more directly challenge oppressive political and social structures, both through the mind as well as through the heart, and additionally to serve as catalysts for potential social and political changes in the context of cultures and their histories.

Peru

Juan Acha, the Peruvian art critic, might see text-based art as a means of more robustly engaging with issues of identity and cultural heritage. He might view text-based art as a way of successfully exploring the intersections between language, culture, and history, and he might be interested in the questions of how and why text-based art can reflect upon, mirror, and critique specific cultural contexts, while also pushing boundaries and subverting expectations, in a way that engages the viewer by exploring ambiguities and encouraging interpretations.

South Asia

Pakistan

Quddus Mirza is a Pakistani art critic who has written on contemporary art practices in Pakistan as well as South Asia. Mirza might view text-based art as an art form and as a medium that provides a means of exploring the relationships between languages, cultures, and identities in Pakistan and its society. As with critics discussed above, he might see text-based art as a way for artists to challenge not just contemporary societal norms in Pakistan but also traditional notions of Pakistani art and culture, as well as to create spaces for marginalized voices in Pakistan in relation to Pakistan itself as well as to both elsewhere in South Asia and the broader world.

South Eastern Europe

Greece

Maria Marangou is a Greek art critic who has written on contemporary art practices in Greece as well as Western Europe, and might see text-based art in many of the same ways as other critics discussed above, including as a means of exploring the intersections of language, culture, and identity in Greece both now and historically. And like other critics discussed above, her writings suggest that she might see text-based art as a way to examine and evaluate traditional notions of Greek art and culture relative to contemporary, modern, and possibly also post-modern views.

Western Europe

France

Jacques Derrida, referenced above in the discussion of the American art critic, theorist, and academic Rosalind Krauss, is the prominent French philosopher and literary critic across multiple disciplines who made watershed contributions to Western philosophy as the conceptual founder of deconstructionism. Very broadly, for purposes of this short monograph / artist’s studio paper, deconstruction is an analytic useful for criticizing not only literary texts and philosophical texts, but also societal and political constructs, in an attempt to find or create concepts of justice in those texts and constructs.

Applied here, through the analytic of deconstruction, Derrida might see text-based art as a profound vehicle by which to questions the very idea of meaning itself, a question transcending any one language or any one aesthetic, and approaching questions of the universal. More specifically, he might especially see text-based art as being able to highlight and explore all of the multiple and often contradictory interpretations that can be read from, and applied to, almost any given textual or language-based statement, be it as short as a single phrase or as long and complex as an entire novel—and by extension, almost any given idea or view that may be expressed in those texts.

As the founder of deconstructionism in all its applications, Derrida would likely be most interested in text artists who are most adept at avoiding the didactic and declarative, and rather are able to experiment with ambiguity, multiple interpretations, and viewer interaction for meaning-making to its fullest, and thereby challenging traditional modes of artistic expression that focus only on the intent of the artist, and not the participation of the viewer in the act of interpretation. As such, Derrida might see the influential American text-based artist Jenny Holzer as at the vanguard of the possibilities of text-based art, given that Holzer’s public space installations worldwide, both large and small, offer viewers intentionally ambiguous phrases and sentences that are not just open to multiple readings, but which also invite those multiple readings in some of the most profound areas of human thinking, interactions, and questions of morality and ethics.

The French literary critic and philosopher Roland Barthes, who has written on semiotics, the study of anything that can make meaning through any of the human senses, has, relevant here, written on the relationship between semiotics, language, and culture. He might see text-based art as a means of exploring the cultural and political significance of language in making meanings, and also exploring how and why those meanings might be interpreted by different recipients the same way or different ways. Also relevant here, many of his writings appear to emphasize the possibility of, and the intellectual utility of, the ability for text-based art to create multiple meanings, ambiguities, and interpretations, even the simplest of texts, including even short phrases, one word, or even a character-symbol—or even a sound of a word or a letter. Loosely from his writings, Barthes would arguably see the most meaningful of text-based artworks as those being made by artists who experiment with language in a self-reflexive manner, inwardly and introspectively, using language to question the very nature and qualities and possibilities of language itself, such as the influential American text-based artist Lawrence Weiner, particularly as to his text works that provide written instructions to viewers on how to create a specific piece of art as an theoretical exercise and experiment in the exploration of language itself and, the ability of language structures to make, record, and transmit meanings to recipients.

Germany

Erwin Panofsky, the German-Jewish art historian, who wrote about the modern study of iconography, the Renaissance, and meaning in the visual arts, including the 1955 book “Meaning in the Visual Arts,” might have used his three strata for evaluating subject matter or meaning of text-based art. For Panofsky, his process was to look at and consider (1) the primary or natural subject matter—what we see at first; then (2) the secondary or conventional subject matter—the meaning of what we are seeing, including its references; and then (3) the tertiary or intrinsic meaning or content—such as, why did the artist decide to create the art in just this way, and what are other signals as to complete meaning? Panofsky might consider this third level, or third strata, to be most important in text-based art, because it might allow the viewer to look at text based art not as an isolated movement in art, but as the product of the environment in which is developed in a particular place over time and history—in order to answer the ultimate questions, for a piece of art, including for a piece of text-based art, of what it all means—and, most importantly, echoing Rosalind Krauss, what are all the possible things that it could mean when the viewer completes the work?

Italy

Achille Bonito Oliva is an Italian art critic known for his engagement with contemporary art practices in both Italy and Western Europe. Like many of the critics discussed above, Oliva might view text-based art as a means of exploring the relationships and interactions between human languages, cultures, and identities of peoples in Italy and in surrounding countries in Europe and the Mediterranean region. He might also see text-based art as a way to challenge deeply-rooted traditional notions of Italian art and culture, and to juxtapose them against contemporary Italian norms, and Western norms, in cultures and societies.

Conclusions of Part 1

To be clear, these overviews are only short summaries of just a few of the writings, theories, and criticisms of these art critics, curators, art theorists, art scholars, and artist-critics, who in turn are just a few of the experts and thinkers in these areas and fields worldwide. That said, based on research of them so far, my tentative conclusions about global text-based art include that—despite often fundamental and even acute differences in philosophical systems, thinking systems, religious influences, and political, economic, and social structures and assumptions, text-based art is (a) evidenced as an art form almost everywhere on the planet for (b) many of the same philosophical, artistic, and concrete reasons.

Broadly speaking, those reasons appear to be that text-based art—loosely and broadly defined here as any visual art that uses words, language, characters, or language-symbols in some way—affords artists, no matter where they are globally, across continents, countries, and cultures, an artistic aesthetic and a means of artistic expression that can address, explore, and wonder about:

· Our most concrete and present issues and needs;

· Our most abstract and philosophical questions about the intellectual head and the emotional heart;

· Our questions about our languages themselves; and

· Our questions about art itself, including, what is art?

I think text-based art can be beyond cool—and way beyond deep. It’s because I think a piece of text-based art, and a long-term body of text-based work, can be all of these things, cumulatively, cohesively, even sometimes all at once.

This is what I think, and what I feel, when I say, this is text-based art.

Page 12

B. This Is Text Based Art: Across Many Art Histories, A Global Artistic DNA

An Initial Survey of the Art Histories, plural, of Global Text-Based Art

As to the available books, papers, and websites that leave a reader with the impression that text-based art is unique to certain artists in New York City in the United States in past 60 years, or unique to certain Western European artists in the past 100 years, or similar, such views are not consistent with globally available evidence. Art with words, or text-based art, or art with language, is shown to be a composite of many art histories across continents and cultures dating back to at least 40,000 BC.

[images in .pdf]

Above left -- Depiction of an unknown bovine animal discovered in the Lubang Jeriji Saléh cave, dated to be 40,000 to 52,000 years old. Linguists and anthropologists are currently debating whether such images were not only figurative but also attempts at an early visual-sound-language communication system—perhaps an early form of text-based art. Above right – Oracle Bone Script (Chinese: 甲骨文; pinyin: jiǎgǔwén) which is an ancient form of Chinese characters engraved on oracle bones—animal bones that were used in particular ceremonial acts. Oracle bone script was used in the late 2nd millennium BC, and is the earliest known form of Chinese writing and characters, which involve logograms.

1. As Art Histories

In China, text-based art has an aesthetic tradition and intellectual tradition that is amongst the oldest in the recorded world. Chinese calligraphy, with both beautiful intricate brushstrokes and profound intellectual and philosophical meanings, has been revered globally as an art form and as a manifestation of China’s art histories for over two millennia. Chinese calligraphers also often placed within their works not just philosophical but also poetic expressions, conveying both profound human emotions and human cognitive ideas at the same time through the written character-word as represented in artistic form. Today, many modern Chinese artists have also pushed the boundaries of text-based art, while at the same time making reference to Chinese art history, by incorporating calligraphy and language characters into contemporary art contexts, as discussed in Part 1. These explore the relationships between the traditional and the modern, as well as the interplay of language and image. Chinese text-based art often reflects the country's complex history, politics, and social issues, offering critical commentary on contemporary Chinese society—using express or tacit references to an aesthetic that has existed in China for thousands of years.

In the Middle East, contemporary and modern text-based art has a direct lineage from, and conceptual and aesthetic connection to, another form of calligraphy, Islamic calligraphy, which is considered a divine art form unto itself. Islamic calligraphy often features verses from sacred texts and has been widely used both in antiquity and in modernity in religious, decorative, and architectural contexts. Contemporary Middle Eastern artists continue to draw on the profound heritage of Islamic calligraphy while at the same time experimenting with new forms, new variations, new content, and new techniques. Many contemporary Middle Eastern text-based artists now explore and investigate themes and issues relating to concepts of identity, gender, and politics, using text in different media as a means to express thoughts and reflections on the region's diverse cultural landscape in relation both to itself and as to the broader world.

In Africa, text-based art may be said to have art histories grounded in spoken languages, oral traditions, and storytelling to communicate and impart and receive knowledge. Very broadly speaking, and as will be discussed below, a significant number of African cultures in North Africa, East Africa, West Africa, and Southern Africa have histories of thousands of years of using verbal narratives, language heuristics, and symbols as a way to convey accrued wisdoms, historical information, and cultural, ethical, and spiritual values and beliefs. Referencing this and incorporating this, both overtly and tacitly, in dozens of contemporary African art forms, mediums, and artistic expressions, artists may be seen using text with visual image to address issues such as colonialism, post-colonialism, identity, and social justice, as well as cultural, religious, military, and power structures and power dynamics. Perhaps because of the strength of the language component in many African text-based art histories, many contemporary African text-based artists are creating language-focused works that are particularly powerful and thought-provoking, including conceptual works that challenge conventional notions not just of art itself, but of particular languages—including languages not only African but also of the countries that engaged in colonization of African countries and regions. As such, and again very broadly speaking, text-based art histories across Africa reflect perhaps not a tradition of calligraphy, as seen in China and the Middle East, but rather the spectacular development across Africa of hundreds of linguistic art histories in mediums of sound and speech.

In the broader region of the Mediterranean, North Africa, and the Middle East, with its astonishingly rich cross-border histories of dozens of ancient civilizations, the histories of text-based art—from the hieroglyphs and proto-symbolic-languages of ancient Egypt, to the inscriptions on architecture and pottery in ancient Greece and the Roman empire, among other empires, establish that text has played a significant role in the aesthetic and artistic expressions of the region across thousands of years, as it has in China and across all of Africa, as discussed above. In the contemporary aggregate Mediterranean-North African-Middle East region, text may be said to be most often used to explore themes such as migration, identity, and cultural heritage—referencing and incorporating what text-based artists derive from the region's past, including its mythologies, while also engaging with contemporary issues facing several Mediterranean, North African, and Middle Eastern countries and societies, such as political instability, war, social inequality, gender inequality, economic issues, and environmental. Yet, broadly speaking, text-based art in this region is also known for its poetic, lyrical, and thought-provoking nature, both as to intellectual systems and as to belief systems, and it invites viewers to reflect and interpret at multiple levels on the complexities and nuances that exist throughout the region's past and present in the context of being one of several foundational locations around the planet of initial human development.

In South America, text-based art may be seen to have art histories with somewhat different aesthetic and intellectual foundations than other regions discussed above, in that, broadly speaking, text-based art appears to be deeply influenced by the continent’s unique literary, artistic, and philosophical traditions. Specifically, yet again speaking broadly as a composite, Latin American literature, with its distinct history with respect to concepts of magical realism, and similar spiritual and intangible beliefs, has inspired some contemporary text-based artists to incorporate text into their works not just in literal ways, such as to engage in social or political or economic issues, but also, and sometimes more fundamentally, in unique and innovative ways embracing feelings and beliefs that far transcend the literal, the material, and the concrete. Broadly speaking, due to these art histories on the continent, South American text-based art, while often addressing social and political issues such as inequality, colonization, and cultural identity, is also a means of using references to different cultural histories of magic realism to more subtly yet powerfully challenge dominant narratives, express dissent, and offer alternative perspectives on South American societies and political powers. Because text-based art in South America has art histories of particularly blurring the boundaries between art and literature, and between the actual and the magical, in the broadest meaning of the concept, it has particular qualities that invite viewers to engage with the power of words, literal, metaphorical, and allegorical, in developing the viewer’s understanding of our world—both that which can be seen and which cannot be seen.

For Native, Aboriginal, and Indigenous Peoples, in all regions of the world, hundreds of text-based art histories manifest elements of each of the global and regional art histories broadly summarized above. Again, necessarily for this paper as a very broad composite, these art histories are also, like those in several regions, grounded in the primacy of language—including oral traditions and storytelling—as an aesthetic, a means of communication of values and beliefs, and as a means of imparting, sharing, and retaining collected wisdoms and experiences. Across the globe, dozens of Indigenous peoples and cultures have long-standing and complex art histories, language histories, and cultural histories that are not only in oral artistic mediums, but also in recorded artistic mediums, including proto-languages, or early languages, using symbols, glyphs, and other forms of written or visual communication, marks, signs, and figures as a means of communicating and passing down through time knowledge, history, spiritual beliefs, and both practical and spiritual understandings of, and relations to, other species and the natural world of the planet itself. From these art histories, in contemporary Indigenous art a significant number of text-based artists incorporate text references and symbol references to highlight, assert, and advocate for cultural identity, as well as to challenge false colonial narratives and draw attention to post-colonialization social, cultural, natural, and environmental issues facing Indigenous communities due to the profound misconduct identified with colonializations. As both a matter of content and aesthetic, many examples of text-based art by Indigenous artists may be seen to reference and draw upon these thousands of years of different, yet in some ways conceptually similar, traditional Indigenous languages and histories. Broadly, in doing so, these text art histories of Indigenous peoples around the world afford present day artists an artistic means by which they are revitalizing and reclaiming the Indigenous cultures and knowledge systems that colonialists marginalized or erased by genocides and other means. Such text artists thereby may be seen to be continuing the same conveyance of knowledge, history, wisdom, and beliefs as seen through thousands of years of oral traditions in thousands of cultures worldwide.

On the landmass that is Russia, the art history of text-based art was documented by the Russian artist Kazimir Malevich, who in approximately 1915 created a series of artworks that consisted solely of geometric shapes and words—not that conceptually different from works in the 1920s and 1930s in parts of Europe during the Dada movement and also during the Surrealism movement, both of which also incorporated text into their works in conceptually similar and aesthetically similar ways, often as a means of subverting conventional meanings and creating new associations.

In Central America, the histories of text-based art are also historically a function of, and are still influenced by, not only the diversity of languages and cultures in the region, but also the region’s need throughout its histories, as with so many other regions discussed above, to respond to the profound physical, cultural, spiritual, and philosophical abuses and consequences of colonialism. Reflecting those art histories, contemporary text-based artists may be seen as often using text in art as a form of protest and resistance, addressing social, political, and economic issues facing Central American societies. In doing this, as seen with the contemporary use of other art histories in other regions of the world, a significant amount of text-based art engages through reference to and amplification of cultural folk art from the past and the present, sometimes fused into street art, creating historically referential yet modern and dynamic works that engage with local contexts and communities at multiple levels. Broadly, Central American artists who use and incorporate text do so as a vehicle to raise awareness, promote social change, and advocate for human rights, but through lenses that reflect historical political legacies and cultural traditions.

In North America, Western-centric text-based art histories exist but are profoundly younger than those discussed above in all of the other regions and cultures of the world, each of which long pre-date the Western view now present on the North American continent. In this context, North America’s Western text-based art histories arguably began within only the past 400 years, in the aftermath of two colonialization-genocides, resulting in aesthetic and language elements of art histories and traditions from the landmass of Europe as well as the landmass of Africa. While arguably the marriage of Western conceptualism to text and visual art is a North American and particularly an American art history, evidence from around the world establishes that this art history did not arise sua sponte on its own on American soil or in American minds, but rather draws from, if not expressly or impliedly appropriates, both culturally and visually, text art histories from all over the world, centuries older, each summarized and discussed above. Corroborating these broad observations are the significant number of published sources that treat North American text-based art history as not existing until the practices of current and/or recently living artists such as Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Ed Ruscha, Christopher Wool, Lawrence Weiner, John Baldessari, Glenn Ligon, Joseph Kosuth, Mel Bochner, Kay Rosen, and others from the 1950s to the present, including but not limited to Holzer's ambiguous yet provocative worldwide text installations, and her Truisms series, and Kruger's works that combine text with images to challenge notions of power, gender, consumerism, and advertising. At the same time in America—and again in profoundly recent art history time relative that in China, Africa, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, South America, Central America, and among Indigenous peoples worldwide—the mid-twentieth century also saw in the United States the rise of the Pop Art movement, which often used text in art as a way of commenting on mass media and consumer culture. Artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein incorporated corporate slogans, corporate brand names, and other language from popular culture and advertising into their works, consistent, in many respects, with exploring many of the same questions about the nature of art and the nature of language that other cultures and text art histories had already been exploring for thousands of years, as discussed above.

In Europe, text-based art histories are also comparatively far shorter compared to the art histories of text-based art in the Middle East, Africa, China, the Mediterranean, South America, Central America, and among Indigenous peoples worldwide. Europe’s text-based art histories that are from that continent’s cultures themselves arguably begin with medieval illuminated manuscripts, primarily in religious contexts. Text-based art can be traced back to the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels, and to 16th century in Europe, where artists such as Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbe Younger incorporated text, often with morals in Latin, into their artworks. Dürer's Melencolia I (1514), for instance, is an engraving that combines a depiction, various symbols, and an ambiguous Latin language phrase that has been interpreted in various ways. Holbein's The Ambassadors (1533) depicts objects, symbols, and a Latin inscription that is moralistic. It is interesting to juxtapose such a moralistic message in European text-based art in the medieval centuries with European text-based art five hundred years later, such as some text pieces of the British artist Tracey Emin of the Young British Artists period.

2. As Language Histories

The hundreds if not thousands of distinct text-based art histories around the world for over two millennia appear to demonstrate that, in many manifestations of text-based art among the world’s artists, for dozens of centuries, language is not merely referenced or incorporated secondarily to complement a visual image or depiction, and is not merely a vehicle or tool for communication, but rather, in these art histories around the world, language itself in the art—meaning that on its own, the language element also holds profound cultural, historical, and emotional significance and meanings. Many text-based art histories arguably support the view that, historically, across time and across geographical areas and cultures, text-based art not only communicates about a subject matter, idea, or emotion—but also communicates something about our languages themselves, and the common elements of our human language histories. Broadly, the histories of text-based art across cultures and time seem to support the observation that many text-based artists have realized, not just in this century but in many centuries past, that language itself is a power dynamic, and that language, though intangible, can create hegemonies of existence, belief, thinking, and values just as powerful and as long-lasting through history as the locations of bodies of water and as the strength or size of militaries. Similarly, in these diverse text-based art histories worldwide, it seems to be that text-based artists worldwide had realized, long before the contemporary-modern period of the last century, that, just as language can be used to bridge, bond, and understand, it can also be used to inflame, isolate, and divide—and also to confuse, mislead, and lie.

3. As Human Developmental Histories

Why do linguists and anthropologists think that humans in so many different places all independently began making text-based art, blending visual communication with symbol, language, and sound communication? The basic answers appear relatively straightforward as to causes but truly remarkable for their essential elements of commonality across thousands of years and across thousands of places worldwide:

Communication and Storytelling: Language is a fundamental element of human communication and thereby the human condition, and text-based art may have emerged as one of several ways to visually communicate ideas, stories, and narratives where for some reason either the visual alone was not enough, or language alone was not enough—either for practical or aesthetic reasons. Just as spoken or written language conveys meaning, text-based art can additionally visually represent language concepts, emotions, and experiences, enhancing and adding to both the efficiency and reliability as well as the enjoyment of the communication of ideas, stories, beliefs, experiences, and accrued wisdoms. Given that in many regions oral storytelling and oral traditions were foundational to the backbones of cultures, text-based art may have served as a visual form of storytelling, allowing early humans to convey information and express themselves through a combination of images and language that perhaps was both more easily understood, such as by younger members of the culture, or by outsiders in neighboring regions having language barriers—but not visual-figurative barriers.

In other words, someone from another group might not know your word for “animal,” but they were likely to know, or be able to guess, your symbol for “animal.”

Ritual and Ceremonial Practices: Many Indigenous cultures around the world have, as discussed, profound histories of using text-based art in their ritual, ceremonial, and information-sharing practices. Text-based art may have been used for being particularly well-suited to convey sacred or symbolic messages, communicate with deities or ancestors, or mark important events or occasions. In these contexts, text-based art serves as a hybrid-visual representation of spiritual or ceremonial practices, combining the power of language with visual aesthetics to convey deeper meanings and significance, including intangible elements not well-captured by either images or words alone. Again, the idea that the marriage of language and visual is additive—that each enhances the other, and thereby a new and more complete whole is made, is arguably an artistic dialectic created by Indigenous peoples around the world thousands of years before Hegel, in Germany, added the concept to the Western philosophical tradition.

Record Keeping and Documentation: Text-based art may have emerged as a way for groups, religions, cultures, and others to record and document important information, accrued wisdom, details of past events, and anticipations of future events, including pending celestial occurrences based on prior recorded observations. Early humans may have used text-based art to create visual records of their daily lives, or their group’s activities, successes, and failures, such as relating to a hunt, or a type of animal or plant, or to communal activities. Text-based art may have also been created and used as proto-maps or other forms of visual documentation to represent and communicate not just intellectual knowledge, and not just beliefs, but empirical and objective facts about the environment, such as locations of animals for food, dangers, and water sources.

Symbolism and Representation: Given that modern languages are used worldwide to represent and symbolize ideas, concepts, and emotions, text-based art may have emerged through experimentation in regions across dozens of centuries as a way to visually represent abstract, intangible, and inchoate concepts that were perhaps too speculative, too theoretical, or otherwise too difficult to convey solely through figurative images. Not everything can be well-captured or well-shared in two dimensions by the physical acts of creating lines and curves. By combining visual elements with language elements, early humans could create a more nuanced and layered representation of their evolving thoughts and beliefs, and their observations of their evolving emotions and their possible meanings. Text-based art may have been used as a form of visual symbolism that was advanced beyond proto-symbols, allowing humans to record, convey, contemplate, and evolve increasingly complex meanings and messages through a combination of images and language that more fully captured and reflected what evolving human brains were starting to produce all around the world in our earliest recorded and pre-recorded times.

Finally, Aesthetic Expression and Creativity: Many linguists and anthropologists hypothesize that, if humans universally have a natural or innate inclination towards artistic expression and creativity, it follows that, universally, text-based art may have emerged as one of many forms of emerging aesthetic expressions in each region and land mass of the planet, purely as a function of human creativity—perhaps an early precursor to the notion of art for art’s sake—allowing early humans to explore and experiment with the visual possibilities of language, and, conversely, the language possibilities of aesthetics. Both conceptually and as applied, text-based art can be seen from this perspective as an early form of visual poetry, or perhaps even a visual form of lyrics without music, where the arrangement, style, and aesthetics of text and character-symbols become an artistic expression in and of itself, apart from any utilitarian purpose for the individual or the group.

In other words, just like I think that text-based art is super cool, maybe early humans did too.

Caveat

To be clear, to my understanding, no one in any scientific field or area of academic study knows as fact the exact causal reasons or chronologies for the emergence of text-based art in human histories around the world. Experts from art historians to linguists to anthropologists to archeologists will likely debate this and similar topics forever, for sound reasons. Further, generally speaking, it’s a mistake by reductionism to look for just a small handful of causal reasons for something in human history—the mathematical probabilities are that dozens if not hundreds of identifiable factors contributed to the developments of text-based art in each group, culture, region, and landmass. Also, at some point, you just have to go with the joy of it—incredibly, humans all over the world with no connection to each other all came up with spectacular variations of this beautiful form of art that blends in infinite ways some of the most beautiful things humankind has ever created—visual art and language. This reminds me of one of the first text-based pieces I made, about something I had suddenly remembered from Whitman—after I heard all the learned astronomers, he wrote, with all their facts and charts, I went outside, and just looked up at perfect silence at the stars.

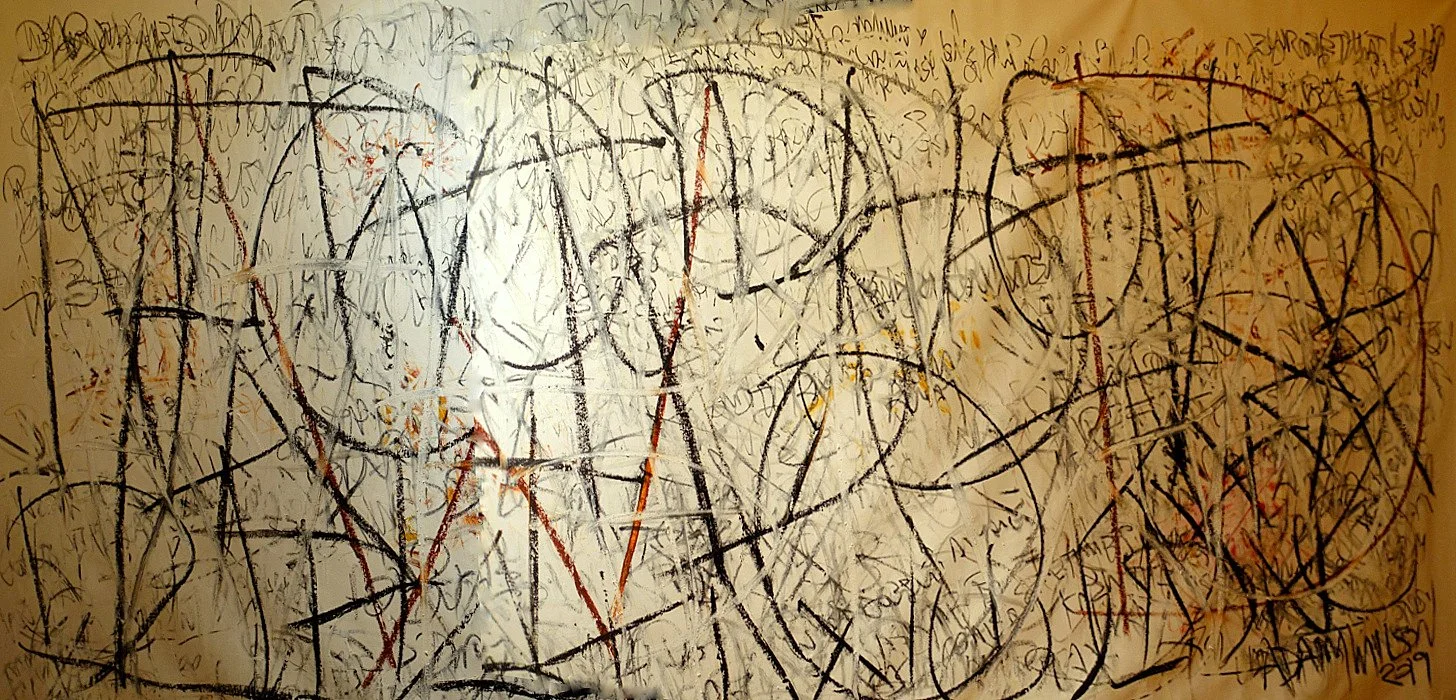

[images in .pdf]

Above left – Whitman’s When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer. Above center – the artist’s second-ever attempt at text-based art, 8.5 in x 11 in (21.59 cm x 279 in), ink on paper, 2014. Above right – a subsequent early personal writing system work of the same text, 8.5 in x 11 in (21.59 cm x 279 in), graphite pencil on paper, 2016. In this last work, the artist’s loose handwriting became unreadable as a result of overlapping layers of the repeated substantive text.

Conclusions of Part 2

One, when condensed to the shortest of factual sentences, the quantity, quality, and diversity of worldwide text-based art over the course of recorded history, and before, is staggering and fantastic: In ancient China, though calligraphers such as Wang Xizhi and Su Shi, as well as in ancient Japan, through the calligraphy art shodo as practiced by artists such as Kukai and Miyamoto Musashi, as well as in Korea and Vietnam, calligraphy and its derivations were considered a high art form and was often used to convey poetry, philosophy, and religious texts. In the Middle East and ancient Islamic cultures, art calligraphy decorated buildings and art objects, and conveyed religious texts and poetry. Ancient Islamic calligraphy is known for its elaborate scripts and intricate designs, with its most famous calligraphers perhaps being Ibn Muqla and Ibn al-Bawwab. In ancient Hinduism, ancient Indian texts, such as the Vedas and the Upanishads, were similarly illustrated with intricate and decorative text-calligraphy-images. Similarly, in Buddhism, ancient Buddhist sutras have been found illustrated with calligraphy and artwork throughout Asia, with notable examples from Japan, China, and Korea. In ancient Africa, as referenced, many ancient and traditional African cultures used text and calligraphy their art, such as the Nsibidi script used by the Igbo people of Nigeria. And in North America, long before 1960s New York City and conceptualism, Native American cultures on the continent were using conceptual symbols and pictographs to conceptually convey stories, ideas, and knowledge and belief systems, including the Navajo sand paintings. In South America, ancient civilizations such as the Incas and they Mayans used hieroglyphics and script, not that conceptually different from those across the world in Egypt, to convey written language as part of their visual art forms. In ancient Egypt, hieroglyphics were used to convey written language and were often incorporated into works of art, such as sculptures and murals. Hieroglyphics were also used to convey religious texts and stories, and were a cornerstone of Egyptian culture and identity. And in South Asia, traditional art forms such as Madhubani painting and Thangka painting often incorporated text, text-symbols, and script into their designs. These art forms often conveyed religious and cultural stories and symbols, and are still practiced in some areas of South Asia today.

Two, one can see the continuation of these art histories worldwide. Just as a few examples, Frida Kahlo in Mexico often incorporated text and verses of poetry into her visual works to express her emotions and experiences. Guillaume Apollinaire was a French poet of Polish descent who pioneered the use of visual calligrammes in his poetry, in which words are arranged in a visual pattern to create a specific shape or image. The Iranian artist Shirin Neshat references the calligraphy tradition by using not just text but also calligraphy in her photographs and videos to explore issues of gender, identity, and cultural displacement. In India, the artist Ganesh Pyne was a painter within the last century who often incorporated text and script into his works to convey a sense of narrative and storytelling. The artist Lee Ufan, associated with both Korea and Japan, is a contemporary artist who often incorporates text and calligraphy into his minimalist paintings and sculptures to explore ideas of language and communication. These are just a few of the aesthetic connections between text-based art histories and text-based art now worldwide.

All of these global text-based art histories: This is text-based art.

Page 18

C. This Is Text Based Art: How Will We Evaluate It As Words and Images Change?

Potential global standards and criteria, both now and post-AI.

1. Who, and now what, gets to make text-based art?

There is now a fundamental question of access and authorship in the context of human art and human language arguably surpassing the revolution started during the Holy Roman Empire around 1440 with the printing press.

For the entire history of our species until now, human beings were the sole source of text, symbol, and language combinations with semiotic meaning. With not just the development of but now worldwide access to AI language models, machines can now be prompted to generate coherent and convincing text and language combinations on their own—and soon human prompts will be unnecessary. This shift in authorship raises deep philosophical questions, and, in most nations, foundational property and related legal questions about the authenticity and originality of text-based art. If an AI language model generates a work of text-based art, is it truly an original creation in the human sense of the word, or simply a derivative product of pre-existing code and data sets? And does that even matter if, in the art market, like any economic market, there is a willing buyer? The question of authorship quickly raises difficult questions related to conceptions of value, worth, and meaning itself.

It seems to get very deep awfully fast. Arguably, compounding this, some human philosophical constructs aren’t even equipped to handle the questions. For example, many philosophical systems of thinking currently prevalent around the world never posited the existence of anyone else besides humankind.

2. In the context of artistic appropriation and mimicry.

An easier entry point may be through the analysis of appropriation, plagiarism, and mimicry. Here, one challenge that AI poses to traditional standards and criteria for evaluating text-based art, and any type art, is the diversity of approaches and techniques that AI can offer. AI can be used to generate text that merely copies or mimics traditional styles, or a particular artist’s style—or, on the other end of the spectrum, AI can be prompted to create entirely new forms of language and language-visual communication. These too raise questions of value and worth, as well as questions going to notions of quality and questions of what is, and will be, “good” art or “high” art, as compared to notions of “kitsch,” in a normative or objective sense as opposed to just a market sense. From the related legal perspective, aside from long-existing property and more recent copyright concepts, it is possible that trade secret concepts in the modern intellectual property context might still be useful—but has an artist who has publicly shown their work of text-based art already in that act disclosed their trade secret, such that current law, absent change, cannot and will not protect that piece of text-based art—or the artist’s unique “look and feel”—the artist’s intellectual or emotional art practice process—from machine use? Particularly where a machine lacks the ability to form the requisite legal intent to steal or misappropriate? Again, it appears to get very deep awfully fast.

3. In the context of aesthetic and linguistic possibilities.

On the other hand, the text-based art possibilities with AI are breathtaking. AI can be used to analyze almost infinite amounts of text-based art, visual, and language data, incorporating everything from over 40,000 years of human activity—and generate new language patterns, new language structures, and new language meanings. The only handbrake on this might be the ability of the viewer to comprehend and interpret these new languages and meanings. Yet AI might then provide an immediate solution: Instant translations of the real-time new languages and text-based artworks, through separate interactive art and language chatbots that could field a viewer’s questions—and possibly manipulate the set of possible interpretations in response.

4. What is Meaning? What is Language?

This comes in some ways full circle to the fundamental intellectual and philosophical questions that text-based art is particularly well-suited for exploring: What is meaning? What is language? Can either one be truly shared with accuracy? Or be truly trusted? Likely, while trying to come to terms with these questions, humans will at some point—and it will vary by jurisdiction and nation—develop both (a) market-based economic ways for valuing text-based art in the context of AI, and humans will also develop (b) government-based legal standards the various conflicting property interests involved. On the economic side, the market will do what it will, while on the government-legal side, the eventually-settled-upon legislative standards and criteria will likely balance (i) the unique property challenges of AI-generated language and text-based art, (ii) the unique fair use and commercial opportunities presented by AI-generated language, and (iii) in that process, concepts such as artists’ rights, copyright, trademark, trade secrets, misappropriation of trade secrets, authenticity, ownership, and sanctioned monopolies for set durations might be modified—or might not. The blending of art, language, aesthetic, ownership, and related property questions will be fascinating for many art lawyers, intellectual property lawyers, collectors, galleries, and institutions such as museums. An additional reason for this is that legislation and judge-made common law always lags behind what humans are actually doing at the time. Query how far the law will lag behind now that it is not humans but machines that are setting the pace.

5. Universal Languages

Even more difficult, query philosophically and in terms of our collective humanity what happens when AI, in making a body of work of text-based art, or when otherwise prompted, creates a new language that either by intention or by acceptance replaces the prevailing languages that are the common denominator political and economic languages of the globalized planet. Which raises the question of whether AI will finally be the thing that brings to humans a universal language.

[images in .pdf]

Above – Between 2019 and 2022 the artist created a short series of text oil paintings exploring universal words and universal sounds in relation to text-based art as possibly supporting elements of a universal language. Research indicated that the word-sound “huh” is thought by linguistics and anthropologists to be both (a) a universally uttered and (b) a universally understood sound—but one that is ultimately (c) lacking the ability to convey complex information and ultimately (d) open to ambiguity. As a conceptual foil, the artist later painted “use” to document his research that, while all humans universally use tools and other things, the word would not be considered universal as to sound or as to meaning, as it has over twenty ambiguous usages. Above left – “Is It Social Interaction Or Inborn Structure And What Does It Mean To Us All,” 2021, oil on canvas, 86 in x 60 in (218.4 x 154.3 cm). Above right – “To Use, Of Use, Been Used, Plus Twenty Or So More,” 2022, oil on canvas, 86 in x 60 in (218.4 x 154.3 cm).

[images in .pdf]